This is the second essay of the exhibition series “Kharkiv School of Photography” by Tatiana Pavlova. The Kharkiv School of Photography is not a physical school but a collective of photographers who began working together in the 1970s and continue in different formats until today.

Tatiana Pavlova.1980 – Faculty of Art History at National Academia of Fine Art and Architecture, Kiev. Ph.D. Docent of Art History chair in Kharkiv State Academy of Art and Design. Curated art exhibitions since 1988 in Ukraine, Russia, Slovakia, Germany, USA. Author of essays on Photography of Ukraine in the History of European photography in the 20th century. Author of books and articles about Ukrainian art and photography. Lectured on Ukrainian photography in Kharkiv, Kiev, Moscow, Bratislava, Poprad, Warsaw, New York.

© Evgeny Pavlov. Selfie with the wife. 1988 (from Total photography)

© Evgeny Pavlov. Selfie with the wife. 1988 (from Total photography)

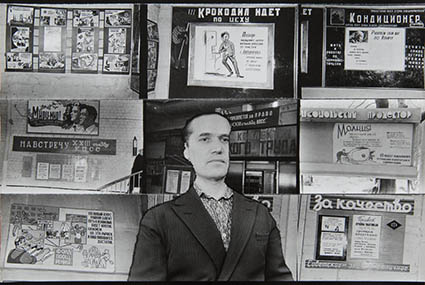

In their early, “communal” period the Vremya collective, and the Kharkiv photographers loosely allied with it, created a basic visual language system in their art. Later, they fleshed out their initial ideas, embracing a more comprehensive approach. The period between the late 1980s to early 1990s was a time of great change and transformation in the Ukrainian society as a result of the so-called Perestroika (“Rebuilding,” a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in Leningrad and popularized by the media) and the de-facto collapse of the Soviet Union. At that time, the Kharkiv photographic school was enriched by a new generation of authors, who brought in a great variety of topics and techniques. They were Victor Kochetov, Roman Pyatkovka, Sergei Solonsky, Igor Chursin (connected with Vremya); the more classic-centered Igor Karpenko, Leonid Konstantinov, and Grigory Okun; plus Vladimir Ogloblin and Vladimir Bysov, who were more interested in the evolution of representative cityscapes and travelogues.

(Image right: Magazine Photo (Paris), 1989 , # 262 )

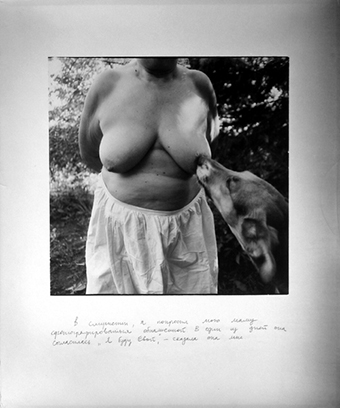

In 1989 the French magazine Photo published material on the Soviet photographic avant-garde of the 1980, mostly represented by Kharkiv authors (Boris Mikhailov, Eugeny Pavlov, Roman Pyatkovka, Valery Krey), with a name that came a half-century late: “The Pioneers of the Red Avant-garde” (“Ils sont les pionniers de l’avant-garde rouge”)1. It was a characteristic Western appreciation of the Ukrainian underground as contrasted against the historical 1920s avant-garde. But in spite of the value of such analogies for a heterochronic model of historical red avant-garde research, the pictures published in Photo belonged to the green avant-garde. If we were to analyze the whole image and style of the Kharkiv photo school (known as “brutal”), we would clearly see the green hippie line running through it. Naturalization/natural instinct behaviors were the main principles of this period. These motives were concerned with being free from mechanical stereotypes (to quote Viktor Tupitsin2) of the social life that was characteristic of the Soviet society.

(image © Oleg Malevany. Metamorphose. 1991 )

© Photographs by Boris Mikhailov, Roman Pyatkovka, Eugeny Pavlov in Photo (Paris), 1989

© Photographs by Boris Mikhailov, Roman Pyatkovka, Eugeny Pavlov in Photo (Paris), 1989

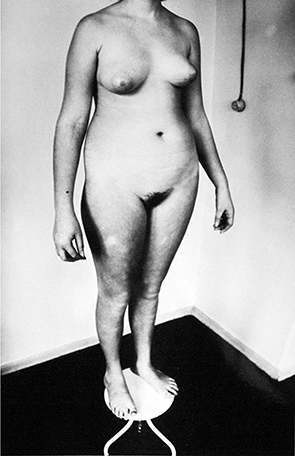

The very fact that it was Ukraine that happened to be a “broken link” makes one recollect the regularities described by Karl Jung (nowhere else but in the godforsaken Nazareth) or Gumilyov’s “passionarian overheating.” Being a symptom of ill health, Ukrainian photography could not help but expose what Mikhailov called “a fan of pains” where each and every author was able to establish their own limitations to what they deemed unbearable: Boris Mihailov’s social pain, Oleg Malevanny’s aesthetic pain, Eugeny Pavlov’s physical pain. The only exemption seemed to be Alexandr Suprun, whose photographic art developed what might be described as a “positive grotesque.”

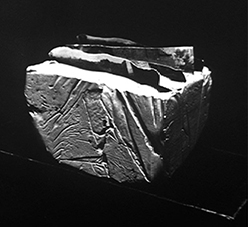

Alexandr Suprun. The gift. 1992

Alexandr Suprun. The gift. 1992

There can hardly be an art as revealing of that status quo as the art of photography. Today, there is no denying the scandalous part it played, together with cinema, in the formation of a monstrous phantom-producing machine of the Soviets. One has to admit that it was nothing else but photography that served as a testing field for visualizing the contemporary sign system, which was especially significant for the system, because “visualization admits fewer ambiguities” (G. Potcheptsov3).

(iimage: © Boris Mikhailov. Luriki. 1985)

A powerful stream of existential feeling determined the “want of truth,” which was to become the driving force of photography in the last moments of the Soviet Union’s existence. At this time there came into being a new hero: the common man and his surroundings – first imaged in Mikhailov’s 1970s photography4 . It is this rational truthful photography that brings us to the codification for the given discourse. The phenomenon of a common man presented itself in a form of somnambulistic existence as well as one of reflection of ideological mythos which was absolutely unintentional, and that is exactly where the turning point of transformation from the real to the unreal, and vice versa is to be found: it is to be found in such a sacred place as an average person’s photo album. That’s where the trick (or the dual ambiguity of a “Soviet citizen’s” cultural typology) lies.

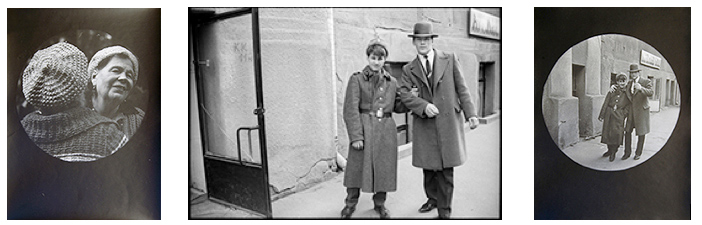

Images: Vitas Luckus (left) .Leonid Pesin, Vitas Luckus, Guennadi Maslov in Vilnius, 1985 (right)

Images: Vitas Luckus (left) .Leonid Pesin, Vitas Luckus, Guennadi Maslov in Vilnius, 1985 (right)

Anonymous amateur photography was first discovered as a form of art in the Soviet Union by Vitas Luckus (Lithuania). He was the first to introduce found photographs into the art of photography. Luckus placed these found images in a higher cultural context by imparting certain aesthetic qualities into them which were missing in the original source (the family album), but he never used the features immanent to amateur photography—innocence, experience and naiveté, which illustrate and define a person’s life. These qualities found in the family album were brought to the forefront and emphasized in the work of Boris Mikhailov. Mikhailov must be given credit to his courage that is grounded in the fact that he introduced the lowest forms of anonymous images into the “art” of photography. In this respect he can be called the founding father of this approach termed “Lurikу” (complimentarily restored and retouched portrait photographs), imitating their kitsch look and making it one of his aesthetic principles.

In the late 1980s, this layer of photo culture became a new paradigm of art in Kharkiv, a new system of values with a complete inner structure. Sub-personal foundations of this metaphoric language were presented as personal, as ones to which the world of a person is confined, which found its manifestation in an ironic or playful attitude.

Image: © Eugeny Pavlov. From Life of a Factory, 1992

At this time another Kharkiv artist, Eugeny Pavlov, first turned to anonymous photography, having inherited a sackful of films from his brother, a factory photographer who was left jobless after the Perestroika. Pavlov used this material in several of his projects, such as The Energy Portraits (1989) and Life of a Factory (1990). Sequences arranged to mimic the layout of a factory newspaper contained veiled allusions to hagiographic iconography, while the Honor Roll portraits spoke of a duality, as if they were just false fronts hiding a deeper mystical reality. At that time, Pavlov’s documentary and staged works finally became two distinct genres, although still connected by a two-way bridge to exchange techniques.

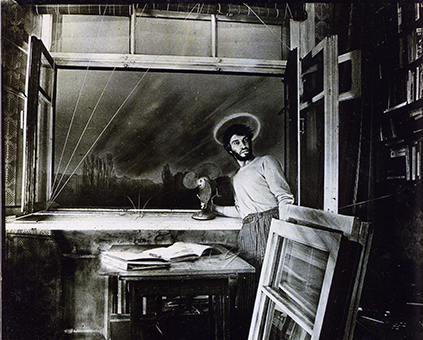

Image: © Eugeny Pavlov. From Archive Series, 1965–1988

Pavlov’s Archive Series, based on straight photography, claims a long timeline (1965–1988) and an expansive geography. Within this “photo novel” characterized by a random plot that constantly changes depending on how one organizes the pictures there are unbreakable clusters of images unified by image content, such as “sleeping people,” “round objects,” or “agricultural” series. The marginalia of Pavlov’s photography not only found their morphology in this imagery, but also shared a specific formal technique of introducing color retouch to black and white photographs. Here, the mechanical faults, dust, and scratches that are normally edited out are highlighted by color markers. This new technique, somewhat reminiscent of tachisme or action painting, is not confined to an exclusively cultural context. Pavlov saw the unavoidable film defects as a stream of coded information, a message from the world of microscopic particles intruding into the photographic process.

Image: © Eugeny Pavlov. Blatari Gospoda (The God’s Proteges), 1989

The graphic stylings first realized in the Archive Series were intentionally copied in Pavlov’s 1989 Blatari Gospoda (The God’s Proteges). This series, presented as a panorama where each shot flows into the next, is overlaid with intrusive graphics, like white noise on a TV screen. It is an expressive gesture, simultaneously destroying traditional concepts about photography and giving it a new value. Fragmenting space with lines and strokes echoes the archaic language of ornament.

(Image: © Victor Kochetov)

But what is the meaning of this macroform full of vague subjects that bring to mind the rhetoric of Soviet posters and monumental art? It is no accident that the latter is symbolically dismantled. The series symbolizes the collapse of the Soviet fresco as a tearing-down of a monumental Wall, an ideological maze with a monster at its dark center. It is all the more important for the fact that monumental art made sacral by Lenin (e.g., Campanella’s City of the Sun) was, in Soviet aesthetic, opposed to photography (“monumental is not momentary”).

Another artist who was molding the path of the Kharkiv photography was Victor Kochetov, whose contribution to the formation and realization of the idea of photographic neo-primitivism can hardly be overestimated. “If photography is really an art,” says he, “it must surely have a kind of folklore of its own.” In quest for the latter, the end-of-the century photography produces a mirror-like reflection of the appeal of primitivism in early 20th-century paintings. Although neo-primitivism may seem to be the leading trend in Kharkiv photographic art, by no means can it be called a mere genre reproduction. The trend goes far beyond genre limitations, to represent a far wider scope of phenomena. In a way, this is an amazing—in its completeness, sincerity and coverage—encyclopedia of the Soviet Mythos. With Kochetov, this will be Soviet reality itself, i.e., the continuous absurdity with a tint of brutality. What he creates, or rather reconstructs, is the basic, popular “readymade” images, wherein he exploits Ukrainian archetypes as if extracted from popular national magazines with their poor print and prettiness on parade. The latter he highlights with additional coloring. The “lurics”—or “portraits for the poor” (such was the term Victor Kochetov coined) acquired a broader meaning.

Another artist who was molding the path of the Kharkiv photography was Victor Kochetov, whose contribution to the formation and realization of the idea of photographic neo-primitivism can hardly be overestimated. “If photography is really an art,” says he, “it must surely have a kind of folklore of its own.” In quest for the latter, the end-of-the century photography produces a mirror-like reflection of the appeal of primitivism in early 20th-century paintings. Although neo-primitivism may seem to be the leading trend in Kharkiv photographic art, by no means can it be called a mere genre reproduction. The trend goes far beyond genre limitations, to represent a far wider scope of phenomena. In a way, this is an amazing—in its completeness, sincerity and coverage—encyclopedia of the Soviet Mythos. With Kochetov, this will be Soviet reality itself, i.e., the continuous absurdity with a tint of brutality. What he creates, or rather reconstructs, is the basic, popular “readymade” images, wherein he exploits Ukrainian archetypes as if extracted from popular national magazines with their poor print and prettiness on parade. The latter he highlights with additional coloring. The “lurics”—or “portraits for the poor” (such was the term Victor Kochetov coined) acquired a broader meaning.

© Igor Chursin

Igor Chursin brought a new aspect to this direction by playing around with primitive and dramatized imagery in his photos of Kharkiv bohemians. Some of these portraits bear zoological names (e.g., “Bears”). He found a great use for the hypertrophic quality of photography that can turn an ordinary person into an idiot, a depraved man, a wise man, or a saint. Halos, candles, and other religious paraphernalia appear in the pictures to drive the point home. Further, the matrix of Eastern sacred imagery quite naturally merges with the Honor Roll in a kind of nirvana.

(Image: © Roman Pyatkovka. From Phantoms of the 1930s, 1990)

Roman Pyatkovka’s anonymous photographs in his series, Phantoms of the 1930s, are a different category entirely. There is nothing ironic about these. They are eerie, sculpted copies of an alien culture. It is no incident that the artist later changed the series’ name, adding the emotionally charged word Holodomor (The Great Famine)—a horrible sign of the time. Pyatkovka took up photography in the late 1980s. Following in the footsteps of Vremya, he merged Mikhailov’s documentary techniques with Pavlov’s drama, transforming and developing them according to his own vision. He imbued his pictures with the negativist energy of late-1980s’ youth movements, creating a number of series, such as The Wrong Picture, Leaving the Herd, The Maternity Ward, I Come from Childhood and Adultery. Here is how Pyatkovka described his photographic vision: “Some photographers use the viewfinder to frame a piece of reality that they find interesting. Others favor a more cinematographic approach arranging pictures in a certain sequence and flow. I try to create an environment and populate it with people who will act out the situation I’ve got in mind.” Pyatkovka’s fiction (what he has referred to as “directed”) photography was about making the person in front of the camera play a role. Another fictionalizing element in his photos was coloring, as in The Maternity Ward.

© Roman Pyatkovka. The Maternity Ward, 1989

Some of his series examine “adult” vs. “adolescent” games and the inevitable conflicts between the two. Roman Pyatkovka uses mass production style in his work, which is partly irrational. Crowds of monsters and ghouls inhabit his images of hard-to-imagine orgies. Voluptuousness and destructiveness are keys to understanding his pictures as a manifestation of the Dionysus.

The brutal elements of reality as seen by Kharkiv photographers are typical of the aesthetics of “admiring the landscapes of decay and failure” (A. Yakimovich5), characteristic of the 20th century. This aspect is evident not only in the subject matter, but also in the way they emphasize the coarse texture of the street, in the atypical staffage of their “photo veduta,” in the dispirited urban fauna.

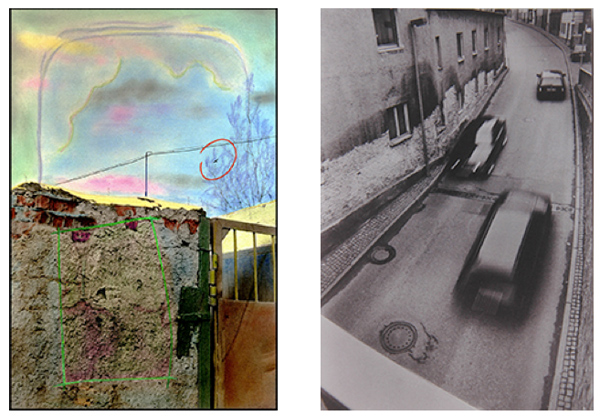

© A. Makienko. Autum, 1990s © A. Makienko. Untitled, 1990s

© A. Makienko. Autum, 1990s © A. Makienko. Untitled, 1990s

It should be noted that the Kharkiv photographic community actively explored the post-Soviet mentality. While Pyatkovka and Chursin exposed urban realities through provocative games, Anatoly Makienko offered to “reform” the outer space via the inner one. His 1989 series, The Autumn, is unified by coloring and a passion for geometry. His works of the 1990s, although somewhat “idyllic” in their unexpected depiction of landscapes of historic entropy embodied in Constructivist buildings, bear the mark of technocracy so typical of Kharkiv. The series of photographs taken in a German town is a special explication of the subject of “compositional environment.” Here, the motivation behind “transforming space” is an exaggerated geometricity, a rational dryness of urban exteriors. The way to avoid such defects lies, according to the author’s creative vision, in adopting dynamic point of view or angles. For example, the view “from above” is used to open up a wide expanse of space. This technique effectively transforms the narrow empty streets of the German town that seem to absorb all the petty routines of everyday life with hardly a sound.

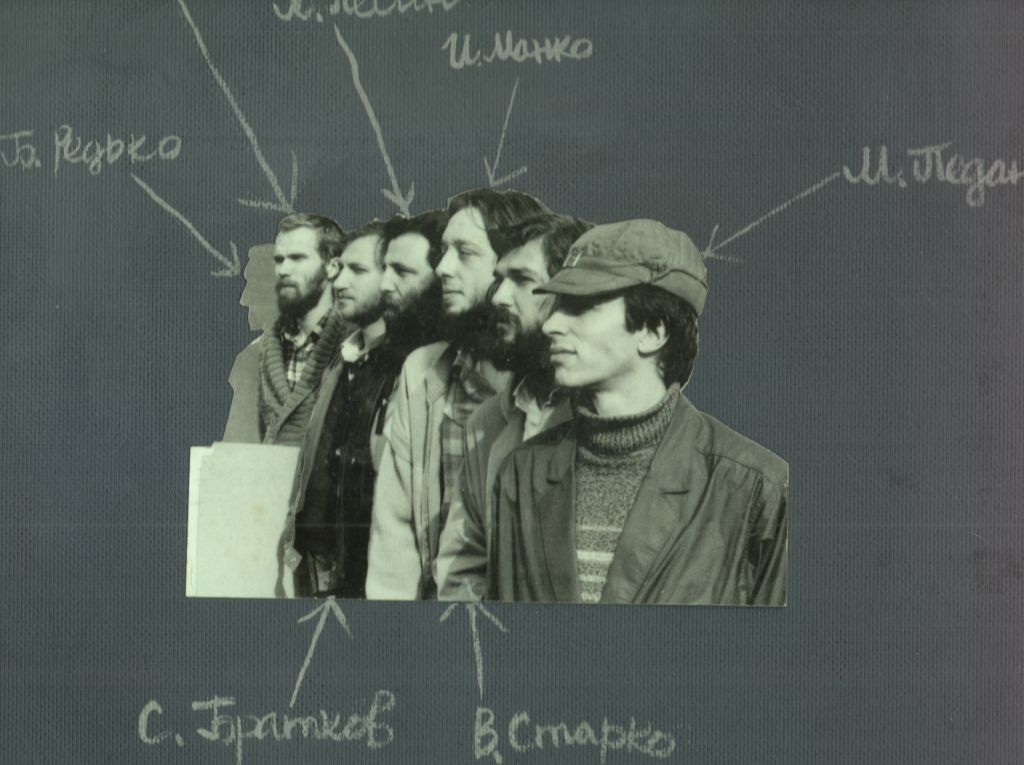

© The Gosprom group

The surge of new strengths in the field of documentary photography was noticeable in the case of “new wave” photographers. This genre can be perceived as the Gosprom group’s manifesto. The group was initially founded in 1984 as Kontakt (“Contact”) and met at the Builders’ Palace of Culture, where Guennadi Maslov worked. The group consisted of Guennadi Maslov, Misha Pedan, Vladimir Starko, Igor Manko, Leonid Pesin, and Boris Redko. After the collective was joined by Sergei Bratkov and Konstantin Melnik, they changed their name to the Gosprom.

It was through the efforts of these ambitious newcomers, and in particular Misha Pedan, that the end of the 1980s saw two photo exhibitions, F-87 and F-88. It was the zenith point of the second wave of Kharkiv photography. The shows took place in the Student Palace located at the “Gigant,” one of the first student campuses in the U.S.S.R. In the spring of 1987 it hosted a free-for-all exhibition of artists of various genres, the first of its kind in Kharkiv. And it was there, later the same year, that Kharkiv photographers first emerged from the underground to take part in the F-87 exhibition curated by Pedan. Those first public outings were real political statements, as witnessed by the visitors’ responses; some days attendance reached over 2,000. The first show lasted ten days, the second only four; the official reason for shutting them down was “fire safety.” The two exhibitions displayed works by different generations of artists who emerged from working underground together, including Boris Mikhailov, Alexandr Suprun, Oleg Malevany, Eugeny Pavlov, Anatoly Makienko, Sergei Solonsky, Victor Kochetov, Roman Pyatkovka, Grigory Okun, Sergei Bratkov, Misha Pedan, Vladiir Starko, Igor Manko, Leonid Pesin, Konstantin Melnik, Boris Redko and many more.

(Image above: .© Guennadi Maslov. 1990)

One cannot help but admire the courage shown by Pedan, who lost his job as a result. His social consciousness and dedication to photographic documentary realism were balanced by a delicate artistic personality. Pedan’s favorite buzzword at the time was “fine,” which emphasized the special nature of his works comprising the series If Winter Comes Tomorrow, shown at F-88. The name alluded to a militaristic Soviet poster “If War Comes Tomorrow” and the crude sloganeering that dominated the art of Social Realism.

Other photographers in this “fine” school of the 1980s (as contrasted with the “blow theory” of their predecessors) were Vladimir Starko, Igor Manko, Konstantin Melnik, and Sergei Bratkov, with his trashy subjects, such as metal jar lids captioned “Not all that glitters is gold.” Unlike Bratkov, however, Pedan passed over the explicit gestures and wild expression of the 1990s. What did we gain from the new documentarian approach developed by Gosprom? By capturing the ordinary (and thus, true) reality, the photographers fulfilled their wish to deal with the predictable and the popular. Thus, the quasi-language of documentary became a meta-language. (Image above: .© Guennadi Maslov. 1990)

(Image: ©.Konstantin Melnik.The end of 1980s)

Many of Gosprom’s methods and techniques were inherited from their forebears. For example, a partially “obscured visibility” is a frequent motive in both Vremya’s and Gosprom’s works. Often it takes the form of a fence with people glimpsing through slits (Konstantin Melnik). In Pedan’s works the obstacles are more complex, manifested in unfolding opaque layers that create broken barriers, such as a police cordon in one of the pictures. But even the endless lines of passengers on the Kharkiv subway that make up the series Metro, corresponded to the idea of a close, confined space.

© M. Pedan. Untitled, 1980s

© M. Pedan. Untitled, 1980s

In contrast to the ideas of Vremya with their aggressive strategies and their “blow theory,” Gosprom’s representations—projected as they were on a different, less intense reality—had a less affective disposition. Still confined to a narrow social network (albeit broader than that of Vremya), they used photography as a way of sending and receiving messages to the viewing public that described everyday observations of the dynamic process that was known as Perestroika.

Left to right: © Grigory Okun. Untitled, 1980s © Misha Pedan. Untitled, 1980s .© G.Okun. Untitled, 1980s

(Above image: © V. Starko. Untitled. 1980s)

A typical feature of Gosprom and other artists allied with the group was that individual snapshots were not meant to be taken as finished works of art. Starko’s, Maslov’s, Melnik’s, or Redko’s pictures were not epistles but rather letters or even notes from some local, private correspondence. It was an exchanging of messages that called for some kind of internal response, but also more tolerant communications with society as a whole. This becomes apparent in their parallel street views, when different artists capture the same locale, creating an echo-chamber effect. A striking instance of this is the duplication of subject matter in works by Pedan and a non-Gosprom photographer Grigory Okun, where they both photographed the same two drunk guys. The snapshots contain enough realistic details that it becomes easy to understand the entire scene. It takes place near a coffee shop on Garshin Street that had its own clientele—people with cultural leanings, photographers among them. The focus of the shot is a “demob” celebrating his return home from military service with a friend. Unlike Pedan, Okun chose the unusual tondo format to frame his pictures, thus distancing himself from Gosprom with its documentarian course, appealing to the artistic form, shaping the meaning of his message.

(Image right: .© Boris Redko. Lady with a Lapdog, 1980s)

Vladimir Starko’s pictures follow in the expressive vein first mined by Vremya. However, his reporting approach has a special module. When his shots document the surrounding reality, he composes them using large objects, as if following a still-life algorithm, shooting architecture as if it were a vase of flowers. In this sense, he offers an additional representation of Kharkiv’s psycho-continuum.

A smoother style can be found in documentary photos by Boris Redko, who later complemented snapshots with surrealistic drawings. Note how, in the collective photo portrait of the Gosprom group, his profile is added to the collage as a drawing, signifying his second instrument.

.© Konstantin Melnik. Untitled, end of 1980s.

A sophisticated irony characterizes lightly colorized works by Konstantin Melnik.

Thanks to the works by Starko, Pesin, and Redko in the late 1980s the Kharkiv community learned to better understand itself and its underlying attitudes. The increased communicability provided by constant monitoring of the social context by these photographers was welcomed and appropriated. Gosprom’s multi-level photographic streams brought about great transformations, mostly concerning new ways of overcoming global stress and new methods for neutralizing the aggression released in the course of learning the bitter truth about the Soviet reality.

© Leonid Pesin. Hospital, 1980-1985

Such were, for example, the explicit photographs taken at a maximum-security prison for children and teenagers taken by Leonid Pesin, who left a promising career in science to pursue photography. Despite the humane nature of Pesin’s photographs, the series was so shocking in its very subject matter that the prison warden who originally permitted the filming, in the end, confiscated almost all materials, including the negatives. Pesin managed to salvage only some of that work.

© S.Bratkov. No Heaven.1995

Gosprom’s repertoire also included more low-key, closed projects that seemed at first glance to be far removed from the social, such as Igor Manko’s utopian series of the late 1980s. We cannot be absolutely certain, but it makes sense to assume that it was in response to these that Sergei Bratkov created his series No Heaven in 1995, following the common eschatological attitudes of the late 20th century. The pictures in this series were mostly taken at his parents’ cottage, in the garden—as perceived through the prism of childhood memories. Bratkov’s series rejects the allusion to the images of the biblical Garden of Eden and the Heavenly City mentioned by John the Evangelist in his Revelation, and later by St. Augustine. Like most dystopias, Bratkov’s No Heaven is about a specific, localized utopia. We believe he was referring to the two series by Manko, The Abandoned Garden and Childhood Memories which heralded the second wave of the Kharkiv photo school.

(Image above: .© I.Manko. Childhood Memories. 1988)

Igor Manko’s name for his series Childhood Memories is chronologically conflicting. The basic temporal feature of photography is the present, while memories belong to literature, possibly painting, but not photography. Photography exercises its memorial function by serving as a reminder. For instance, this series largely centers around the “mother and child” imagery. However, the playful child is actually not the artist, but his son, and the child’s mother is not the mother of his memories. The pictures depict family scenes at a countryside cottage, where Igor Manko spent his childhood. But the name of the series prevents it from being merely a broadcast of events; it places a lens in front of the viewer, which transforms the picture and places the focus of impression squarely in the past. The image of the son is the focal point in this retrospective fantasy. It draws the author’s ego, the source of his memories. The nostalgic atmosphere, so important in awakening memories, is created through the classic technique of photo “aging,” making it sepia-toned. The pictures look worn with age. Like faded memories, they erase the line between real and make-believe; father and son are no longer simply similar, they become identical, all differences washed away. All this is achieved through “straight” photography, using no collaging, unlike, say, the famous memory-based series A Look at Ancient Photography by the Lithuanian photographer, Vitas Luckus (who was an important influence on Kharkiv artists). Luckus inserted “memories” by literally pasting fragments of old photos, mostly portraits, onto his snapshots. Far from being hidden, the collage technique was further emphasized by the ragged edges of these inserts. Igor Manko’s series draws you into the pool of memories with its accent on the signs of approximation, applying color intensifiers, and thus diffusing the contours, as if the artist used an ancient photo lens and neglected to correct its aberrations. Diffused light, blurred lines, toning of the pictures—all this is used to send the viewer into the past, into childhood. These methods are based on a simple analogy: old lenses signify olden days. The resulting blurry imagery reminds us that the opposite of memory is oblivion.

© Igor Manko. The Abandoned Garden, 1988

Plot-wise (in exploring “the fall of man”) and object-wise, The Abandoned Garden serves as a twin to Childhood Memories. The rich flora and the typically wide open spaces of countryside gardens, the lack of any fences or markers delineating properties—all this prevents us from identifying the subject matter of Igor Manko’s pictures as the Garden of European tradition. These images contain a distinct Eastern flavor, a Borgesian context wherein the illusionary garden with “vanishing” or “divergent” paths follows laws entirely different from those of botany or agriculture. It is the “abandoned garden” of childhood memories. A sense of liberation, an illusion of new breathtaking vistas, a chance to breathe freely, to be free in one’s actions, memories, and thoughts—this is the second implication of the abandoned garden. Here is a pathway into a magical garden, a freedom to cultivate your own little garden anyway you like: for example, “recalling” an Eastern garden to serve as a model.

The semantic modifications of “apparition” (typical of the logic of “fuzzy concepts”6) are characteristic of Gosprom’s output. We find them in Manko’s memorial series, where they are associated with uncertainty and demand of their viewer to meditate on what he or she sees. What make it all possible are the lightness, transparency, and plastic subtlety of the photos. At the same time, they show a different garden, not the one that thrives in childhood memories. This garden is abandoned, spent, and empty.

Thus, in the poetics of Kharkiv “gardens” in the last third of the 20th century the garden comes to represent dramatic conflict, or vain hopes. Cycles of “moratoria” (such as Bratkov’s No Heaven) add a new loss to the ever-growing list—hopes of paradise regained. And while some art projects present the garden as perfect, this perfection takes place in a wholly utopian dimension.

(Image above: © Sergei Bratkov. Parcel, 1993)

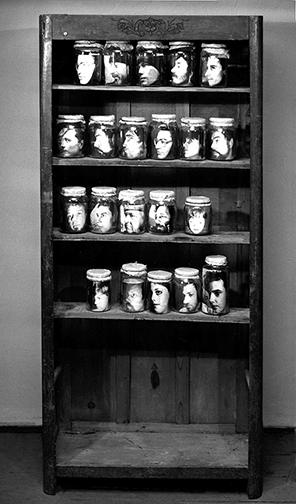

Sergei Bratkov first emerged on the Kharkiv art scene as a photographer, joining the Gosprom collective. Bratkov’s early works, despite documentarian leanings, are nostalgic and even passéist. Like Man Ray, initially Bratkov preferred painting (and even cinema), but his works in those realms, as opposed to his photographs, do not possess what Barthes termed the punctum. The energy plane used in his paintings was supported by a collage of symbolic materials, such as coal, although not in its usual role as a drawing material. Later in his career, Bratkov found use for all three arts in assemblage and various performances. Among these are objects in which photography is used for practical purposes; for example, The Cupboard (We All Eat Each Other, 1991) filled with photographs inside water- or air-filled glass jars; The Parcel, with snapshots packed randomly into the concrete mass; The Frozen Landscapes (1994), a tribute to the 45 homeless who froze to death one cold Kharkiv day. The photograph becomes a memento, a souvenir of existence.

Having enlarged the documentary sphere to a risky extent, almost all representatives of this movement made some significant changes in their lives at the beginning of the 1990s for economical, rather than political reasons. Some left to deal with other kinds of photography, other changed their jobs, and some left Kharkiv. In this last group were Boris Mikhailov (Berlin), Guennadi Maslov (USA), Leonid Pesin (Australia), Sergei Bratkov (Russia), and Misha Pedan (Sweden). It is important to note that they did not abandon photography and thus, the Kharkiv School of photography’s achievements evolved in different geographical contexts. The appearance of Ukraine on the world map of photography happened largely due to their work. Thus, for instance, it became obvious that, presenting conceptual landscapes of Stockholm in the Swedish Institute, Misha Pedan still represents Kharkiv, and what is more, they are molded by Kharkiv. This special way of presenting views with characteristic dark gray dominating colors is a mark of Kharkiv artists.

(Image: © Sergei Bratkov. The Cupboard (We All Eat Each Other), 1991)

In 1989 the Union of Ukrainian Art Photographers was founded including regional departments in big cities. Gradually, state support of these departments was reduced to zero. In Kharkiv, which still remained the most active center of Ukrainian art photography in the 1980s, the Panorama Experimental Art Center (1987-1991) was founded. The Photo Department was headed by Boris Mikhailov and the Art Department by Tatiana Pavlova. Kharkiv became the center of international photography relations at that time. Panorama offered an alternative exhibition space, albeit mobile rather than permanent. Shows took place at unusual locations, such as the Institute of Metrology, “Houses of Culture”, and the new, still-unfinished Opera Theater that resembled a sci-fi hi-tech ruin.

A basement office in the bedroom community of Saltovka district suddenly became a center of underground art activities, especially photographic ones. In the late 1980s it attracted artists from Moscow, Minsk, Kyiv, and abroad. Thus, in 1987, formerly underground Kharkiv artists received financial backing for exhibitions and a communication center led by photographers (Boris Mikhailov, Eugeny Pavlov, Sergei Solonsky, Roman Pyatkovka, Victor Kochetov, Sergei Bratkov et al.), thanks to Panorama. Almost at the very beginning this collective was joined by a number of underground painters. Each Panorama project had a clear curator’s concept and was accompanied by critical texts (“You’ve got to formulate a theory,” Mikhailov told me), thus launching the process of archiving Kharkiv contemporary art. In 1988, Pavlov won a trip to Bulgaria in a photographic contest and brought back an article about himself published in Bulgarian Photo as well as an invitation for the Vremya group and other Kharkiv photographers to attend the prestigious International Photo Vacations festival. It was their first collective show abroad.

Later, Panorama organized the first showing of underground works at the Art Museum (Pavlov’s exhibition in 1988); participation in the exhibition of American, Estonian, and Kharkiv photography in the famously nonconformist Moscow At The Kashirka gallery accompanied by my lecture on the Kharkiv School of Photography (1989); and the second foreign exhibition (Gallery 4, Cheb, Czech Republic, 1990). This, and other events organized by Panorama, had an influence on contemporary art in Kharkiv (among other things legitimating abstract painting), and made a name for Kharkiv photography both in Ukraine and abroad. Every day we would flock to the basement on the outskirts of Kharkiv, where a kind of continuous conference took place, where problems of new art photography were discussed, and new mixed projects developed utilizing both painting and photography (The Free Vernisage, Kharkiv Opera Theater, 1991).

The mid-1990s saw a regrouping of the Kharkiv photographic community. The Gosprom collective fell apart. Mikhailov joined up with Bratkov and Solonsky to form the Rapid Response Group, which devoted itself to provocative photo-based art activities. In those days the center of attention gravitated more toward Kyiv, not least because some artists moved to the capital. In Kharkiv, the integration of photography into art occurred through painting, as evidenced by the language of “interartscape” created by Eugeny Pavlov and Vladimir Shaposhnikov.

.%201988.jpg)

© Boris Mikhailov. “Panorama” at International Photo Vacation festival (Sazopol. Bulgaria). 1988

Notes:

1.Artistes et createures, ils sont les pionners de l”Avangard rouge in Photo (Paris), 1989, #262.

2. Tupitsyn, V. “Nonidentity with Identity: Moscow Communal Modernism, 1950s-1980s,” Nonconformist Art: The Soviet Experience 1956-1986, eds. Alla Rosenfeld and Norton T. Dodge. London: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

5. Pocheptsov, G. Visually as a semiotic phenomenon// Рhotographic image and its function in culture. – Riga: Riga State University, 1988. – Р.35

4.Phrasing of the idea of an ” common man” by B.Mikhailov came next after Ilya Kabakov’s discovery of Gogol’s “little man”, hiding behind the proud myth of the “Soviet people”

5 Yakimovich, A. О двух концепциях культуры Нового и Новейшего времени in Iskusstvoznanie (Moscow), 2001, № 1, p. 41.

6. Lakoff G. Hedges: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts / G. Lakoff // Papers from the 8th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. – Chicago, 1972, P. 183-228.

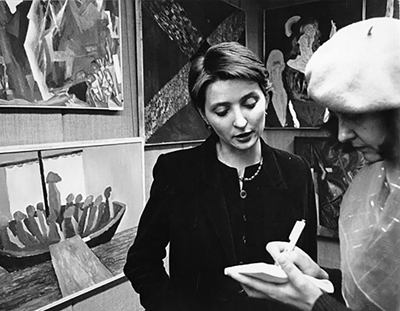

Tatiana Pavlova, 1988, Panorama exhibition

© T. Pavlova